The Vagina Travelogues: Menstrual Musings and Product Ponderings on International Menstrual Hygiene Day

TRIGGER WARNING: This post contains references to menstruation. Do not proceed if you are uncomfortable with the function. Or if you are my father-in-law.

A few hours before we left our house for nine months of travel, I sat on our garage floor amidst small mountains of feminine hygiene products, which I was packing into ziplock bags, pads with wings, extra-long pads for night time, liners, varying strengths of ‘pon, some with applicators, some more eco-conscious without, and a moon cup as backup. I turned a blind eye to to the heaps of plastic applicators that would pollute the earth, gritted my teeth and determinedly ignored the sparkly packaging and brightly colored (plastic) wrappers for the sake of my daughter's menstrual peace of mind. I wanted to leave no possibility of the kid backing out of FULL PARTICIPATION in our trip. Hiking, trekking, swimming, all of it. We were heading off to SE Asia and I was damned sure that we would be well-supplied.

Much to my chagrin, however, I couldn’t make it all fit in my bag.

I found my darling husband standing over me. He knows that, occasionally, my interest preparedness can move me from a “belt and braces” approach to something more akin to “belt, braces, duck tape… mmm, maybe block-and-tackle, just in case.” Gently and with humor (albeit slightly strained), he helped talk me down, building on the argument of several other friends that product would be for sale in major towns. I re-thought the ratio of tampon to pad, then reworked it again, as the clock ticked, and put what wouldn’t fit in storage. I packed a fair bit more than he thought I should, a bit less than I thought I should. But there it was, and off we went, in peace. That’s marriage in a nutshell, really.

And, as noted above, there are two of us doing this menstruation thing—which sometimes leaves Brian caught between Scylla and Charybdis. However, our travels together have fostered even greater openness in our family (not just N and me, but all three of us)--an honesty and humor that I treasure.

In that spirit, I share the broad outlines of our adventures in product sourcing.

Japan. I won’t deny my satisfaction in having our proverbial coffers full. I still believe that Japanese toilets are so full-service that there is one out there that will change the tampon for you. You’re welcome.

Nepal. We made it through Nepal with… er… flying colors. Regarding facilities: squatty potties and no running water from time to time keep things interesting, and zip locks are our friend for packing in and packing out. I don’t know for sure, but based on some online research it doesn’t seem like it would be too hard to find tampons in Kathmandu, which is teeming with Western travelers and expats.

Thailand? That was a piece of pizza, as the Kiwis say. Chiang Mai is loaded with Boots pharmacies and a lot of Western ex-pats. I recall those days as if I was IN a feminine hygiene ad, breezing around confidently on our Bromptons . . . My supply chain was solid, bathrooms were plentiful. All good.

Myanmar, check. Provisions held, threat level low. Merry Christmas, indeed! And very grateful, because while you may be able to go to one or two places in Yangon to buy tampons, they aren’t sold anywhere else “out of fear that they will tear the hymen and condemn a girl to impurity.” Which gets you thinking.

Laos? Problem. While tampon stocks were holding up, our pad supply was running dangerously low. These things (by “things,” I mean “periods”) tend to happen at the least convenient moments. So, maybe an hour before leaving for the airport, I went out on an urgent search and secure mission. I wandered from one Vientiane pharmacy to another store to a pharmacy, inquiring with feigned nonchalance and getting nowhere. Finally scored a pack of “super” liners before dashing back to the hotel. No tampons on offer, that I could see, but consumption of this resource had been held to acceptable levels and I judged the threat level to be low.

Product deployment, however, required some jury-rigging. While these are “super” for Lao women, they are sub-optimal for a big falang like me. I could have co-opted band-aids from my the first aid kit and had better luck. Seriously.

Western pad on the left, Cambodian model on right--both billed as "super."

Vietnam. We were on scooters, heading to Hue, when another, regrettably urgent, mission was launched. We stopped for lunch and I went a-huntin’.

First, a wild goose chase to one big western-style superstore that turned out to have been knocked down for a new building site.

Then, several little storefronts that stock a really interesting collection of household goods, laundry supplies, and even diapers—but nothing for uterine exsanguination.

Pharmacies? I found dispensing chemists only: each a small counter open to the street with the attendant bored chemist behind it. I balked at the first few because I just didn’t want to go through the process with the older guys at the counters, smoking their cigarettes. Eventually, after a lengthy, google-translate-mediated exchange with a bright and cheery female chemist, I confirmed that pharmacies don't offer these precious goods.

Eventually, painfully aware that my family might be thinking I had been abducted, I hit pay dirt at a down-at-heel, sort-of-grocery-looking, kind-of-tourist-catering shop. Some tubes of sun block, dusty souvenirs, leftover signs reading “CHUC MUNG NAM MOI!” (Happy New Year) but otherwise, the shelves were all half-empty (or, I suppose, half-stocked, but at that moment I was DEFINITELY in a half-empty frame of mind). Though, as in Laos, there were no tampons, there were indeed about eight packages of what were clearly pads, sitting forlornly on an otherwise empty shelf in a back corner. I grabbed the puffiest looking plastic package I could, hoping for larger sizes, calculating that English-language packaging might bode well; I even thought that these might have some vague “eco” value, as the name is “Natural Lady.” Relieved, I rejoined my family, installed said product, and off we went again.

But after a few blocks it, became clear that something was not right down south. Not in the sense that one might expect, but in the sense that I was experiencing… Well, I was experiencing a distinct tingle. A tingle that felt like Tiger Balm.

I have to say that it is quite unsettling to go through an afternoon of that before being able to break out the bags and take stock of the situation, which only brought up more questions than answers.

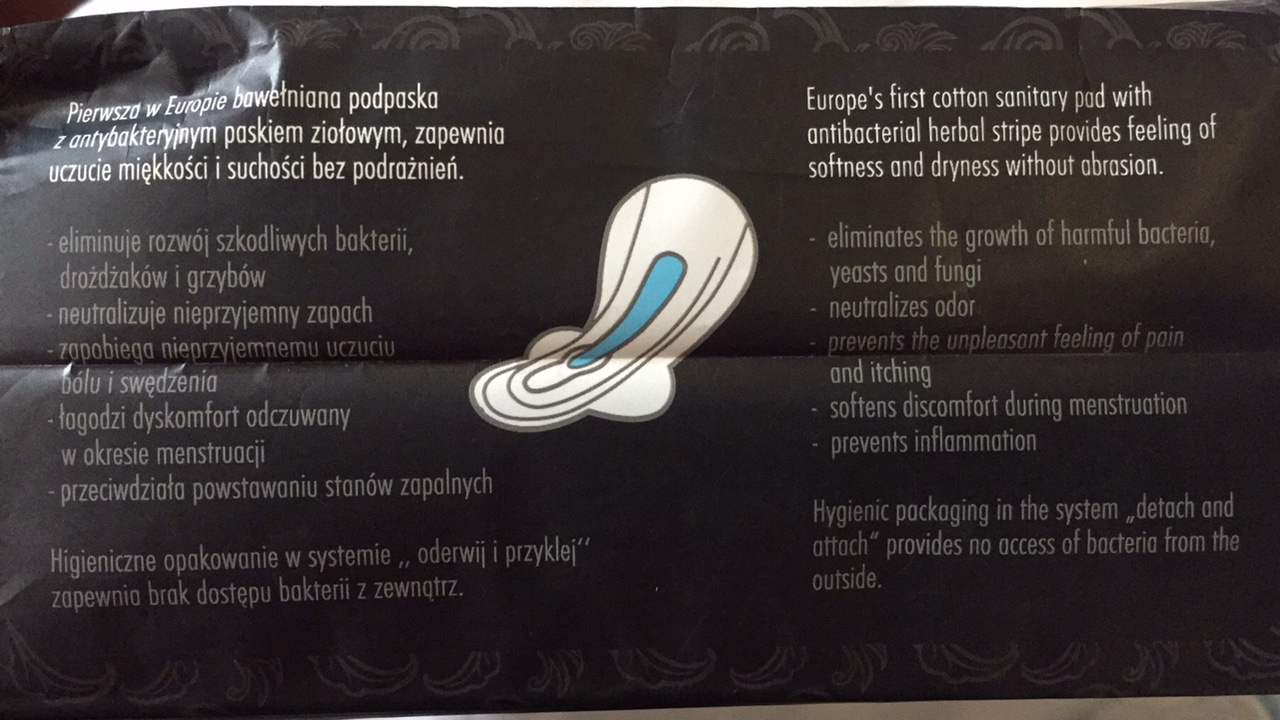

So these are Polish pads. Not pads for polishing, I mean they are produced in China by a company based in Poland, presumably for the Polish market, if the marketing blurbs on the back are any index. Why are they here? Are they inexpensive? Are they bootleg? Come to think of it, the packaging is suspiciously reminiscent of Kotex. . .

But really, the main question is, WHY the freaky little blue strip that makes a person’s hoo-hoo go all tingly? Can that REALLY be “herbal” or in any way “natural”? I certainly agree that it is preferable alternative to abrasion, and indeed all of the other unpleasantness the pad claims to avert.

And who, WHO, exactly, thinks this hoo-hoo tingle is a value-add? Well, the packaging copy—offering more of an ultimatum than a market segment—tells us what the company thinks:

Somehow shaming, prurience, self-help AND fatuous mansplaining are all rolled up in one lumpen catch phrase.

I suddenly remembered an old Kathy and Mo piece on menstruation, which still makes me laugh:

This sketch has stuck with me for years. I love both the absurdity of peddling “freshness” to a starving Russian peasant widow and the sharp notes about what the perception of menstruation would be if in fact men did it. Kathy and Mo highlight the stigma in our own society that still persists: all the sparkly packaging meant to make the tampons and pads look frivolous and festive, like "lipstick". The actual fact of menstruation, that you BLEED, is never acknowledged; have you EVER even seen red ink on the packaging or instructional inserts???

Which made this sign in a NZ campground bathroom stall door totally, utterly riveting:

Seriously, this is he ONLY time I have ever seen menstrual blood actually illustrated in red in any kind of signage or product packaging.

So astonishing!

But in truth, you can’t (OK, well, I can't) think about menstruation as you travel without being curious to find out more about what is going on in the countries you visit. The experiences I outline above are those of privilege and affluence: I am a Western woman moving through these countries at a rapid clip. My daughter and I are lucky enough NOT to be bound in the sticky cobwebs of ignorance, menophobia and often brutal suppression of women (although the GOP seems quite ready to go there).

A little internet searching on attitudes and taboos in the countries we visited was a window on persistent stigmatization of menstruation whose intensity directly correlates to the state of sanitation and education available to girls. These function together in a vicious cycle to keep girls from achieving or even appearing in society. It points to menstrual hygiene management as a basic human right.

JAPAN

Japan has had a policy requiring companies to provide period leave to women since just after WW II. Which sounds helpful, except that companies are not required to provide paid leave and most women don’t take it for fear of being stigmatized or seen as “weak” in a crushingly competitive work culture.

Looking at deeper tradition, Shinto Buddhist writers have strongly held that women are “impure” and “polluting” because of their menstruation, in much the same way that men in other organized religions have claimed, really pretty much ad nauseam.

But here’s one that might be new to you as it was to me: the belief that women can’t be sushi chefs because they menstruate. Yup. Menstruation makes them “have an imbalance in their taste.”

VIETNAM

There is quite decent access to sanitation and sanitary supplies in Vietnam. Women definitely play a stronger role in the labor force and government, and are, according to labor law, allowed to take 30-minute breaks as needed to address fem hygiene or period pain. But some women still believe that a tampon can get lost up there, or that if they take a bath during menses their hair will fall out and they will get dark circles under their eyes.

NEPAL

Nepali women have a horrific go of it in general. Discrimination runs rampant in education and employment, and indeed women are still viewed as more or less trainable chattel in the country. While ruled illegal in 2005, the practice of chhaupadi (isolation of menstruating girls and women for the days of their menses in a hut or cowshed) is a grotesque artifact of this cultural bias that is still practiced in rural areas. It is cruel, debilitating in terms of its impact on school attendance and the well-being of girls subjected to it. They are banished—winter or summer—and few young women have actually died in chhaupadi. They've died from snake bites, smoke asphyxiation, hypothermia, even of simple dysentery because family members are afraid to touch a menstruating person, so they won’t move her to a clinic. . . And, because they are isolated, they are also vulnerable to rape by community members whose attitudes toward blood are overridden by the easy target.

For Hindus in Nepal, there is even a festival for women to ritually purify themselves 365 times, once for each day of the previous year. This, so that they don’t share the fate of the mythical woman who was reborn as a prostitute because she didn’t follow the menstrual restrictions (which extend to brushing a man’s arm in a crowd). It is called Richi Panchami, after that woman.

THAILAND

It is fascinating that in a place where gender identification is more fluid, women are still not particularly well-regarded. Just consider that the oldest and eminently more qualified child of the king was never even considered for the throne on his death solely because she is a woman and therefore unfit to rule.

Signage in temples warns that women are not allowed in ordination halls (because menstruation is seen as polluting, I was informed by one monk). In the Theravada Buddhist tradition as practiced in Myanmar and Thailand, women cannot reach enlightenment—only male incarnations can do so— and of course nuns can’t be ordained.

Beyond the temples to another culturally sacred space, the Muay Thai fighting arena, I found a really interesting blog by a farang (Western) woman fighter that discusses entry into the ring:

“Men always go over the top rope with the mongkol (an amulet, essentially) worn on the head; these beliefs dictate that the head is the highest and most sacred part of the body and the feet are the lowest, most profane, so nothing must go over the head, including the ropes of the ring. Men with amulets on their person or with Sak Yant tattoos can be seen not passing underneath branches, strings, ropes, clothes lines, etc. in everyday life. This is exactly why women go under the bottom rope – our heads cannot go above amulets or protected/blessed objects, statues, images, persons, etc. because by going over them with our heads we negate or destroy the magic. We pollute it. We produce dire consequences or events. So our heads do the opposite, they go nearly to the ground which is the lowest place, down to below where the feet of male fighters land when they climb over the ropes. With universal high/low esteem of the body and space it is unmistakeably a degradation to have to crawl under the ropes as a woman – even though we as western women don’t necessarily feel it. We have the bottom rope pass over our most sacred part, our heads. “

--from Sylvie von Duuglas-Ittu's Muay Thai blog, 8 Limbs

MYANMAR/BURMA

I don’t think it is possible to overstate the role of nat (spirit) worship, astrology, numerology, and arcane superstition in everyday Burmese life. Or, indeed, in the highest workings of government. Woven into the culture and its practice of Theravada Buddhism, which is the official state religion, these beliefs inform and reinforce the stigma of menstruation (and the suppression of women who do it). The breadth and number of proscriptions on women and their belongings and clothing because of menstruation is breathtaking, but here are a few:

In Myanmar, monks collect alms from the people, and not as a supplement; the rice is their food for the day. Women are prohibited from making any physical contact with a monk at any time—but if a woman gives a monk rice alms when they have their period, tradition holds that woman will go to hell.

In villages, women are prohibited from making offerings of food or water while menstruating as it will poison the offering. This applies to major temples AND to the altars in private homes.

In fact, women are not supposed to apply gold leaf to Buddha statues (a common form of offering at some of the grander temples) at all, because they will taint it.

As they might some kinds of food (like pickles).

Husbands don’t sleep in the same bed with their wives if they are menstruating. I think you know who is discommoded in that arrangement.

You shouldn’t shower during your period because it may make you infertile.

Women may "cast a spell" by introducing a little menstrual blood into his food or drink, which will make that man fall (or stay) hopelessly in love with that woman. Blood magic!

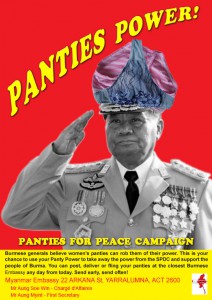

Men and women’s clothing is washed separately, and it is maintained that touching a woman’s undergarments--or even her longyi--will sap a man’s strength. It is rumored that the military leadership would have underwear hidden in the hotel rooms of opponents or foreign dignitaries the night before any negotiations were held, to weaken them. If this sounds far-fetched, consider the Panties Protest of 2007, exploiting the generals’ superstitions.

Because the generals brutally cracked down on any protestors gathering in public, the protest went both underground and international, with the intent to both shame and weaken the power of the ruling generals.

As you might infer from that protest, things are changing in the city with a younger generation more aware and pushing back against the stigma in art and daily life. But that is almost exclusively in the city.

LAOS

Reporting in Laos, which is a recipient of massive amounts of foreign aid, is more formal, with a lot of NGO documentation of a bleak situation. Sanitation is poor outside of major cities, which makes it very hard for girls and women to stay clean, and commercial products are too expensive or not available, leaving rural women to try grass and leaves, or nothing at all.

One researcher noted that some women who try pads are then alarmed because the pads absorb the blood and so it seems as though their flow is reduced. The women worry that the pads are somehow preventing the proper flow of blood, which they believe would accrue in their bodies to make them ill or infertile.

Girls often attend school sporadically and end up missing key gating points like exams or just drop out entirely because they stay home rather than go to school when they have their period rather than be shamed and harassed. Which of course leaves them in at further disadvantage down the road.

CAMBODIA

Same, same, but worse. Against a backdrop of serious poverty and undernutrition, paucity of facilities (like, the lowest rate of toilet coverage in SE Asia), widespread intergenerational PTSD, staggeringly high rates of domestic abuse (1 in 5 women, according to a 2016 UN report), the situation for women is grim. One third of women only hear about menstruation once they have hit menarche, which goes by the term "choulmlob," meaning "into the shade."

Girls are told to keep the cloth from their first period to ward off evil (also handy as antidote to snake bite). They are not to eat certain foods such as sour or fermented foods: no ice water or coconut juice, which might inhibit bleeding.

One quarter of workplaces in the entire country have no toilet. Schools may have open latrines, or nothing at all, leaving girls to go home (sometimes miles away) to chenge pads. Village schools only convene for half-days, so it is even more likely than in Laos that a girl simply won’t come to school if they have their period. And, as elsewhere, when women and girls wander out to seek privacy under cover of darkness, they are prey to assault.

And zooming out from the countries that we visited: one in three people around the world has NO ACCESS to toilets or a sink to wash hands in. This is disproportionately devastating to women and girls because of menstruation and the stigma around it. There are myriad interconnected health and safety issues captured in the umbrella acronym WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene), that are being tackled by small organizations and major NGOs like The Gates Foundation, PATH, and Water Aid. This isn’t news to them. And, intellectually, at least, it isn’t to me. But traveling is a lens on the world, and reflects back to us how much we have, and how much we take completely for granted at home.

We joke openly about our periods, my daughter is unashamed to talk about it with her Dad, and we buy what we need when we need it (or draw from my considerable stockpile). But I am thinking about that collection of misogynist swine in Washington, D.C. There they sit, writing policy on women’s health, leering about women as "vessels," undermining our right to choice and looking at us as a set of pre-existing conditions that they can grope at will. How different is this, really, from the misogynists who declare women unclean and shameful for a biological function that is as normal as sneezing?

I cringe at how much I have taken for granted—including the simple dignity of having my menses in peace.