FUJI-SAN

"Several Japanese resort towns have excellent views of Mount Fuji. Many locals prefer to view Fuji from a relaxing onsen than to climb it's Mars-like surface."

[http://www.japan-talk.com/jt/new/mount-fuji][0]

Top icon for Japan? Bet you thought of Mt. Fuji. The perfectly conical volcano is the highest mountain in Japan, and is regarded as sacred in Buddhism and Shinto (which seem to have a symbiotic relationship in Japan).

Classic, right?

Climbing Fuji became a goal for me when we decided to start our travels in Japan: a kind of pilgrimage, an opportunity to engage with rich national and cultural history, an incredible hike with amazing views. A bucket list item. Brian was slightly less keen, but also saw it as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and embraced it. The young one was already resigned to us ruining her life, so there it was.

And we did it. We booked a tour with Mt Fuji Guides. We rented some gear, bought some gear, worried about whether the kid could do it, talked about it, relaxed about it.

Mythical Fuji

One of the central myths of Mt Fuji centers on a girl from the moon. Princess Kaguya-Hime is found as a baby inside a glowing bamboo plant by a bamboo cutter and raised by the cutter and his wife. Grown up to be unearthly beautiful, she is pursued by legion suitors, whom she rejects by setting impossible tasks. The emperor also falls in love with her and though she won't marry him because she isn't of this earth, they correspond. When her people come and take her back to her immortal realm, she sends him a love letter and a bottle of the elixer of life before she returns home forever. He can't stand the thought of living eternally without her, so he sends servants to "the place closest to the heavens" to destroy the elixir, along with his own love letter, which he has them burn in the hopes that it will reach her. The name of the mountain is thought by some to derive from the word for "immortal." This story is considered the oldest extant prose narrative in Japanese history, but it remains HUGE in Japan, both the straight fairy tale and countless adaptations of or riffs on it: multiple Manga series, films by various directors including Miyazake, even Pretty Sailor Moon, who is actually a reincarnation of Princess Kaguya.

The oldest surviving rendition of this story dates back to the 17th Century,and resides in a British collection, The Chester Beatty Scrolls. As it happens, though, it is included in the current exhibition at the Mori Museum, "The Universe and Art." Which exhibition we went to the day before the climb. It was beautiful and serendipitous. I was excited.

The weather, though.... There has been a storm system sitting on Japan like a cat on a warm tummy, and we haven't seen a sunny day the whole time (mostly ok because it makes things a bit cooler). It has rained a fair bit too--mostly misty-drizzly, but more sturdy than in Seattle. I mean, we even surrendered and bought umbrellas!

On the day of the trip, we woke up in our little apartment and the rain was POUNDING. We trudged through buckets of rain to the Metro, wondering what the hell we were doing and hoping for the best.

At the meet-up, ready to go--or as ready as we will ever be, anyway.

At the meet-up, the guides took the unusual step of offering a refund to anyone who pulled out due to the weather, which was slated to be significantly uglier than is normal in the off-season. No one in the group backed out.

Off we went, into the vans for the drive to the fifth station hut on the Subashiri trail. There are multiple approaches from different prefectures, this one is quite a bit less crowded even in high season, but our group would ascend without seeing any other hikers.

At the Subashiri 5th station, we were greeted by the loamy smell of mushrooms (well, and rain). 'Tis the funghi season! We were served lovely cups of warm mushroom broth and watched as different groups of people took turns emptying their bags and sorting their foraged haul at the front tables.

Mmmmm...mushrooms.

After gathering the poles, backpack covers, and rain gear that we had rented in advance (and hallelujah for those!!!), the group set out to hike up to 7th station hut, Taiyoukan, 1000 meters higher.

A lot of the group, the daughter included, set out at a very aggressive pace. I am more of a tortoise, slow but steady, in my hiking, and Brian very kindly kept with me. Over time, the group pushed farther ahead. N felt the weird constriction of throat heralding over-exertion at altitude, which can be truly panic-inducing. So she dropped back with us and one of the guides stayed with us as we brought up the rear. We chatted about skiiing in Hokkaido, where Matt is a heli- and cat-ski guide in the winter; hiking technique to maximize the ratio of distance covered to energy expended; his growing up in Sweden as a half-Japanese kid; his frustration with Japan's bureaucracy; the beauty of the pink birch trees around us. He told us that Miyazaki had stayed at one of the mountain huts for four months to sketch the clouds for "Castle in the Sky," one of Nuala's favorite movies.

The last of the trees, intrepid young one hiking in shorts (?!).

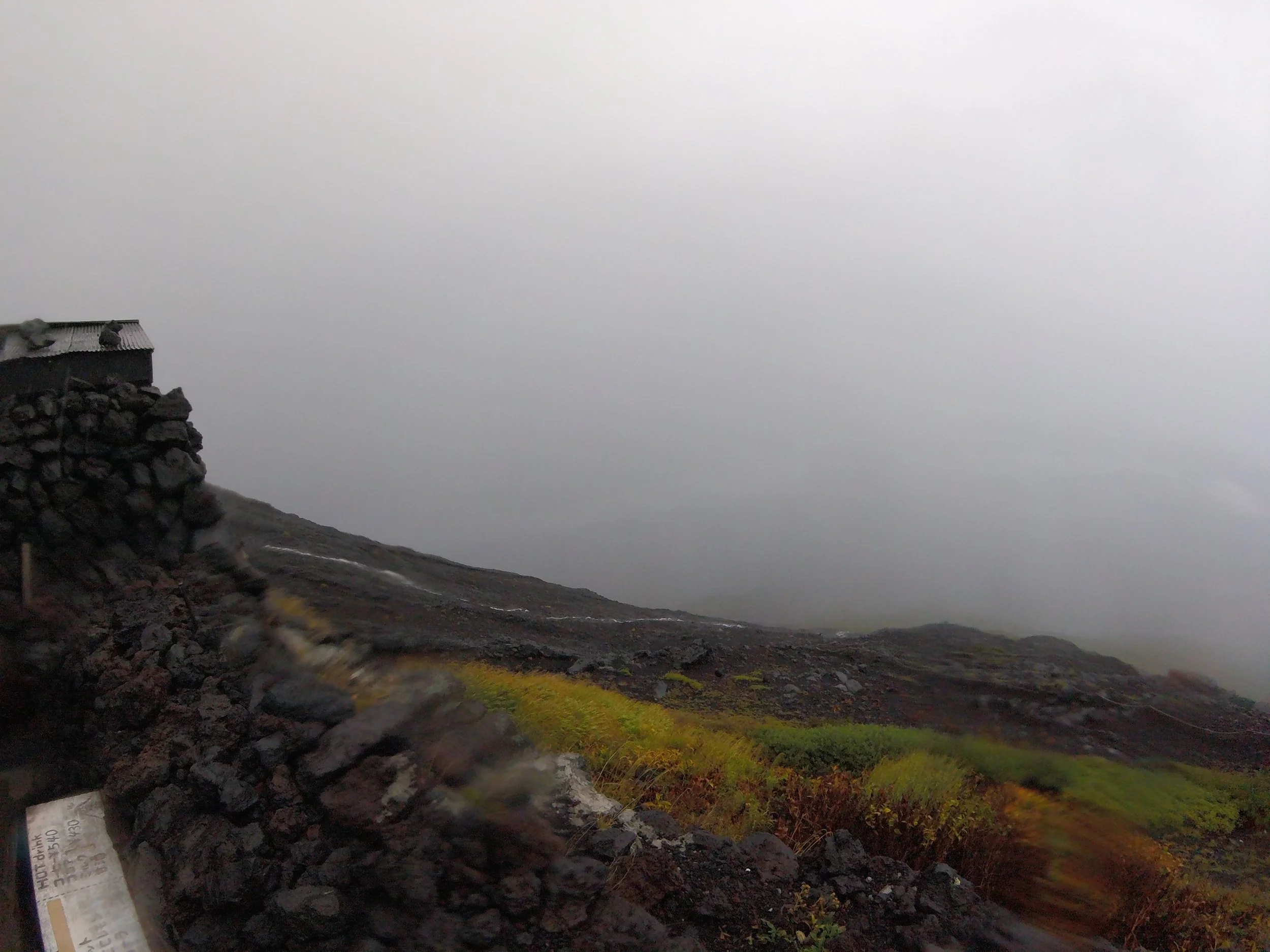

The trees eventually gave way to scrubbier brush and then to a moonscape dotted by tough plants that are bright green in summer but are now turning bright yellow and orange that pops out against the black basalt moonscape. Several times I mistook single leaves on the path to be gold leaf or brass earrings and only saw them as leaves in a double-take.

I had lots of time to contemplate the colors of leaves and rocks on the trail, because the ascent was hard--960 meters vertical in a few hours kind of hard. The conversation slowed and ceased except at breaks, where confirmation of capacity to continue was pretty much the extent of it. It was a slow, metronome-like trudge to climb as the air got thinner. The teenager was a champ, this was definitely the most strenuous hike she has done.

And the whole time, the drizzle came down, working its way in, while the sweat condensation inside the rain suits collected to soak through all our clothes.

And eventually, we reached the 7th hut, Taiyoukan--the only one still open at this time of year.

Taiyoukan, 7th Station. The hut has been in service for about 600 years. The current proprietor is a passionate environmentalist and has installed the only solar array on the mountain--installed only after extended battles with government bureaucrats. Home sweet home for tonight!

This is a bit from the guide book on the 7th Station written by the owner, a burly 70-year old former Japanese Navy man.

Eventually we were mostly dried and fed and warmed by the kerosene heaters (yes, burning inside. . . we think many brain cells may have been sacrificed). We got to watch a little sumo (quite fun to recognize the same fighters we had cheered and boo'd in person a few days before!), and then turned in for a restless night's sleep with the rain pounding away on the metal roof a few feet above and the strains of reggae and house music playing at the front desk.

Then up at 4:30 for breakfast, fussing with yesterday's gear to try to get it a little warmer, a little more dry, and the wait (until 7) for a break in the weather to leave. We had to move fast today, to cover the 830 meter climb and make it to the top before the wind got too bad.

A break in the weather for our departure! That white line isn't frost, it's a silvery lichen that streaks the mountain from here up to the top.

It was that inexorable mist/rain with strong winds, a hardcore incline, and a quick pace, so N decided quickly to stay at the hut for our return in a few hours. This turned out to be very, very sound judgement on her part. One guide turned back with two others in the group within an hour. The trail map here gives you an indication of altitude gain and nefarious switchbackery.

Every little tick is a switchback. We went up on the red line to the right and came down on the red line to the left.

I can't really convey the grinding monotony of the 840-meter ascent. Switchback after switchback, closed in by fog, soaked within an hour, hands numbed, the harsh pull of air in and the dutiful, studied exhalation, one foot/pole placed and lean to shift. Repeat. All of us in a line could have been some brightly colored millipede snacking up a tree trunk. We moved in synchrony, even as we spread out over time.

A little watery sunlight through the clouds part of the way up the second day. Stragglers in motion (yes, that's me in pink).

An hour to the first hut, then other huts in relatively quick succession (each push a little nugget of beauty and hell all unto itself), then another hour. That doesn't seem such a long time when you are sitting comfortably typing on a keyboard, but when you are freezing and bonking and laboring in anoxia, it is a long, long, long-ass time.

I have hiked a lot. This was, hands-down, the hardest one I can remember. The breaks were just a minute or two, we couldn't stop for more than that because it was too wretched. Everyone listened to the guide's briefing in exhausted silence, and we would start off again, each time more slowly. At the last break, the group silence was broken by the sharp snort of a Canadian bearing an uncanny resemblance--minus the humor-- to Steve Carrell. This was in response to the guide's somber warning that we would need to slow our pace in the last hour to get up the trail as it would be getting steeper and the rocks much higher to get over. It was a guffaw that positively bellowed, "How is that possible?"

Shortly after, as we got moving again, the guide warned a fellow who was really struggling that he should really check himself: if he was feeling like he'd used 50% by the time he got the top, he shouldn't be there, because it was going to take more than the remaining 50% to get down.

"Fuck." I thought, "What if you've used 85% to get to the fucking top? . . . What if you've used 95% to get

right fucking here???"

[Note: I think this was at Goraiko-kan on the map, so about 300 vertical meters to go. ]

Don't give up just before the miracle occurs--AA truism.

We shuffled on. It was really cold now, and gusts of wind were like sumo wrestlers picking you up and heaving you feet to the side before you could counterbalance. I couldn't feel my fingers, I was soaked and shivering, only able to take a pull of water by stopping. I could feel my thoughts slow and muddy with the anoxia, and the world was down to rocks and lungs and muscles. My walking felt almost like swimming, slow and deliberate motion through the treacle filling my legs. That last hour of the climb, I was repeating the words as a mantra.

But about 100 feet before the final gate at the top, I was done. For the first time in my hiking life, I was really, truly, totally convinced that I was "a goner". I was just going to sink down and stop right there. It didn't even feel like I was giving up, it just was. It was a fact that I would not make it. A sort of sad fact, in my sluggish brain, but an inevitable one.

And then, on the mountain as he had in life, Brian intervened and posited a different reality. He asked a question, he gave me his support, he showed me a way. And then it was inevitable that I would make the summit.

Schrodinger's cat was alive.

I wept passing through the gate. I am still trying to figure out the mix of emotions I was feeling. And no, hypothermia isn't an emotion.

Relief? Definitely. Joy? That's pushing it. Gratitude? . . . yes. A huge wave of gratitude for everything that has allowed us to make this crazy thing happen--not just the Fuji climb, but all of it: the trip, my life together with Brian and Nuala, quitting drinking, bearing witness to the incredible power and beauty of nature, for the beautiful (and rather worn) body that labored so hard to get me up here. Yes, I think it was almost entirely gratitude, because my eyes are leaking again now.

That's me. I got through the gate and tried to get out of the wind for proper crying in the corner. No go, the wind was inescapable.

Obligatory photo at the top. I am mostly done crying. The shelter is closed so we all shiver, and jam chocolate into our gobs before hobbling over to to crater rim, which we feel compelled to do before getting the hell down.

At the Top of the World

Normally, I imagine, there are congratulations and high fives and stories swapped among hikers. Normally, the tour gives people time to eat lunch and spend 1.5 hours walking around the circumference of the crater. None that--after obligatory photos, we hobbled over to contemplate the crater. Or, more accurately, to confirm the existence of a rope in front of a slightly deeper, gloomier patch of whiteness that we understood to be the crater.

I was still shaking like a leaf, dreading the scramble back down those bloody rocks, wondering how the guide's math worked out if I had spent 105% getting to the top.

Fortunately, the descent back to Station 7 was different (the left line on the map). This is a wide cat track through basalt gravel and heavy sand. Each step was part slide, by intention, back down long switchbacks. The rhythm was similar though, with that same exaggeratedly slow pace, matching the breath and pacing the feet with the poles that were now used more like brakes. Still freezing and sodden, but on the descent.

On the way down, you get a sense of why Miyazake spent four months here sketching clouds for "Castle in the Sky"

The stop at the 7th was brief, but a welcome quick chance to wring out gloves, take a few weary breaths, and collect the almost unwholesomely cheerful and dry offspring. Who shot off like a bunny down the trail (though she followed our family hiking rules and stopped to wait for us at junctions, with a cheer that made my heart sing).

This part of the descent trail is called "Sunabashiri," shown on the map in its literal translation: "Sand Run." No switchbacks, just a straight shot down the mountain. Each step was a partial plant, allowing a wave of gravelly sand to push you downward by several feet further. Again, slow-motion and a steady cadence of motion and breath, for what seemed like a very long time.

At that point, we spread out further in rough groups: the first, including daughter, was with the incomprehensibly nimble and speedy guide, Matt. Brian and I fell into the middle, while Josh, a mellow guide with a slow smile, helped two other struggling hikers well behind.

After the gate that marked the transition from moonscape to forest (the Komitake Shrine, I think), the forest muzzled sound and cut off sight lines, so Brian and I were alone together. We were warm again, the rain had all but stopped, and it felt like more familiar hiking. Our navigation was very gingerly over craggy rocks and gnarled tree roots along a rutted diversion trail. We were exhausted but chatting softly and companionably as we picked our way down. I believe Brian managed to repeat an earlier claim: "this hike will live in infamy!"

We came to appreciate our bodies and our age as we went along, noticing that we are significantly older than anyone else in the group. Indeed, I felt as though I was an old woman (or perhaps a very ungainly beetle). I used my poles more like crutches, first probing and then settling as much of my weight as I dared on each one before shifting my weight to the downhill foot. More than once, going over a rock on the trail, I cautiously eased onto my downhill leg and felt the muscles soften against my will so that I almost sank to the ground.

This sign looks rather like we felt.

Appropriate to be descending "Immortal Mountain" and find yourself contemplating mortality and the sensation of being very old. Feeling in to all those aches and pains, to being bent and gnarled and unsteady, to being so brittle, restricted, and to be so cautious about your movement. Yet it didn't feel morbid. Rather, as the time passed and we got closer to the 5th Station, I realized how comfortable it is to share that vulnerable state with Brian. I could feel, in my bones, the rightness of growing old together with this man. This gallant man, who would offer me his hiking pole when I broke mine 100 meters from the end, and who, when I refused it, would simply telescope his up and walk side by side with me, all the way to the finish.